Harvard Erasmus Lectures I

Prélude a la nouvelle journée, the emergence of Dutch contemporary music

Willem Mengelberg Matthijs Vermeulen

Verhulst,

Zweers,

Wagenaar,

Dopper

..."Who are these people?", you might wonder.

It are the names of Dutch composers who were en vogue in the late 19th- and the first half

of the twentieth century. They were considered to be relevant enough to have their names shine

out from gilded plates on the balcony of the Concertgebouw, amidst their esteemed colleagues from abroad.

The Concertgebouw is the shrine which the Dutch, out of their love of music,

erected in 1888 in Amsterdam. In this acoustic Walhalla, a total of 46 shields bear the names

of their most revered warriors and demigods, who conquered so many a castle in the air for us.

However, there is a peculiar absence, or rather a painful omission, of the name of the best

composer the Netherlands brought forth in that era: Matthijs Vermeulen.

The Concertgebouw is the shrine which the Dutch, out of their love of music,

erected in 1888 in Amsterdam. In this acoustic Walhalla, a total of 46 shields bear the names

of their most revered warriors and demigods, who conquered so many a castle in the air for us.

However, there is a peculiar absence, or rather a painful omission, of the name of the best

composer the Netherlands brought forth in that era: Matthijs Vermeulen.

His music fell on deaf ears with his contemporaries, if it was played at all. Though there

were a few, ardent admirers, it was mostly considered to be awkward, noisy, and unplayable.

In a letter from 1920, while working on his

Second Symphony, Vermeulen wrote to his

friend Evert Cornelis, a pianist and conductor: "I often doubt whether in the first ten,

fifteen years, anybody will love this symphony dearly enough to study it. But I cannot act

otherwise. Because if I do not do what I feel I must do, I can do nothing at all."

Matthijs Vermeulen's words proved to be ominous: It would take until 1953 before his Second

Symphony, titled Prélude a la nouvelle journée, received its first performance.

Nowadays, the disrespectful manner in which Matthijs Vermeulen was frowned upon by his contemporaries,

generally causes a feeling of discomfort and embarrassment. Because in him the Dutch could have found

a composer of international importance and stature. One senses that they missed an opportunity to have

someone to be proud of, perhaps for the first time since Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck in the early 17th century.

Today, Vermeulen is widely regarded as the incarnation of the archetypal unrecognized composer; ahead

of his time, misunderstood and falsely judged, having more of a reputation as a music critic, rather

than as a composer, living a life that largely took place in isolation and poverty, shunned by the

Concertgebouw Orchestra and the music world at large. And though all of this is largely true,

I want to explain to you in this first of three Erasmus Lectures, of which I am by the way greatly

honoured to have been asked to give, that to my opinion things are slightly more complex, and less

one-dimensional. Not only was Vermeulen misunderstood as a composer, he also wanted to be misunderstood.

Not only was he treated as an outcast, it was his desire to be an outsider. I will focus on the music of

Matthijs Vermeulen, and tell you what is so alluring and fascinating about it. I will also shed more light

on the relationship with his main adversary, Willem Mengelberg

, the conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra.

Because, not only is their clash an intriguing piece of psychological drama, but these two men also form the

pinnacle of what musical life in the Rhine delta in the first half of the twentieth century has to offer.

In a letter from 1920, while working on his

Second Symphony, Vermeulen wrote to his

friend Evert Cornelis, a pianist and conductor: "I often doubt whether in the first ten,

fifteen years, anybody will love this symphony dearly enough to study it. But I cannot act

otherwise. Because if I do not do what I feel I must do, I can do nothing at all."

Matthijs Vermeulen's words proved to be ominous: It would take until 1953 before his Second

Symphony, titled Prélude a la nouvelle journée, received its first performance.

Nowadays, the disrespectful manner in which Matthijs Vermeulen was frowned upon by his contemporaries,

generally causes a feeling of discomfort and embarrassment. Because in him the Dutch could have found

a composer of international importance and stature. One senses that they missed an opportunity to have

someone to be proud of, perhaps for the first time since Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck in the early 17th century.

Today, Vermeulen is widely regarded as the incarnation of the archetypal unrecognized composer; ahead

of his time, misunderstood and falsely judged, having more of a reputation as a music critic, rather

than as a composer, living a life that largely took place in isolation and poverty, shunned by the

Concertgebouw Orchestra and the music world at large. And though all of this is largely true,

I want to explain to you in this first of three Erasmus Lectures, of which I am by the way greatly

honoured to have been asked to give, that to my opinion things are slightly more complex, and less

one-dimensional. Not only was Vermeulen misunderstood as a composer, he also wanted to be misunderstood.

Not only was he treated as an outcast, it was his desire to be an outsider. I will focus on the music of

Matthijs Vermeulen, and tell you what is so alluring and fascinating about it. I will also shed more light

on the relationship with his main adversary, Willem Mengelberg

, the conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra.

Because, not only is their clash an intriguing piece of psychological drama, but these two men also form the

pinnacle of what musical life in the Rhine delta in the first half of the twentieth century has to offer.

The focal point of my second lecture, on March 11th, will be the music of the second half of the previous

century, until the present. Whereas the Second Symphony of Vermeulen marks the birth of contemporary

music in the Netherlands and preludes to a new day, it is after the Second World War that Dutch music really

starts to flourish and to gradually take on its own unmistakable identity. I will discuss the music of

Louis Andriessen and Peter Schat and, closely related to that, the rise of ensemble-culture, which played such

a significant catalyzing role in shaping the Dutch musical landscape. And finally, I will talk about various

aspects of my own music in the third lecture on April the 18th. I will attempt to explain to you my love

for vocal music and music theatre, the relation between music and language, or rather: the musicality and

theatricality of language, and will talk about the music of the people who have been helpful and inspiring

to me in finding my own voice, such as my teachers Klaas de Vries and Philippe Boesmans and my mentor

in the land of opera : Hans Werner Henze.

All these matters regarding Dutch contemporary music are of course treated in relation to influences from

elsewhere in Europe and farther away. Music, ephemeral and ethereal as it is, wanders by nature,

so one has to regard modern music in the Netherlands in a context that is larger than that of a country

roughly one and a half times the size of the state of Massachusetts. Furthermore, the Netherlands has

always been a trading nation, which implies an attitude that is open towards the outside world, where

there is more imported and exported than merely physical goods. For centuries, any artist or musician

who was planning to travel from the European mainland to London, was very likely to set sail from Rotterdam.

And often, before boarding the ship, they would give a demonstration of their artistry, if only to cover

their travel expenses. Freedom, of thought and expression, of religion, but also of atheism, forms the core

of the Dutch mentality. It was not merely to tease the British, our main trade-competitors, that the Netherlands

were the first country to recognize the United States as an independent nation in 1776. It was a matter of the heart.

In fact, many similarities are to be drawn between our Acte van Verlatinghe, in which the Dutch

declared themselves free from Spanish rule in 1581, a struggle that would last for eighty years, and your

Declaration of Independence.

One constant element in the Dutch musical history, has been the pivoting movement between the influences

of French and German musical styles and esthetics. Where for example at the 18th century courts of the aristocracy,

French language and music were the dominant factor, it was in the second half of the 19th century the German

symphonic style that conquered most ground. It often seems as if the Dutch were musically torn between two lovers.

As if the French and German influences were like two magnetic poles, and anybody who was attracted to one side,

automatically was to be repelled by the other. This ambiguity, as we will see later on, played a major role in

the controversy between Vermeulen and Mengelberg.

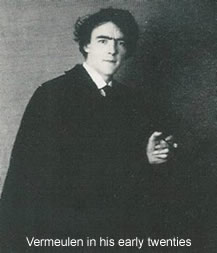

Matthijs Vermeulen, Matthijs being Dutch for Matthew, was born on the 8th of February in the same year in which

the Concertgebouw also came into life: 1888. His place of birth, Helmond, was a small industrial town in the

southern part of the Netherlands, where his father was a blacksmith. Severe illness in childhood made it impossible

for him to do heavy labour, and to succeed his father in his enterprise, as planned. Instead, an inclination towards

the spiritual gained the upper hand, and at age fourteen he went to a seminary, with the intention to become a priest.

There, Vermeulen was thoroughly trained in the music of the old polyphonists of the Netherlands : the masses and

motets of Johannes Ockeghem, Josquin Desprez and Jacob Obrecht, who in his turn had taught Erasmus the principles

of music, when he studied in Utrecht, around 1480. The renaissance masters of the Lowlands made Vermeulen discover

his true calling : music, and their polyphonic world of thought was to be of a lasting influence in the development

of his musical language, later on. His plans for priesthood were dropped, and at age nineteen he went to Amsterdam,

which was then, even more so than today, the centre of musical life in the Netherlands.

Penniless, he listened from behind the hedges to the outdoor summer concerts in the gardens at the back of the

Concertgebouw. These concerts were led by Willem Mengelberg, born in 1871 in Utrecht, who had brought the Concertgebouw

Orchestra to an outstanding level, renowned throughout the world, since he had become their principle conductor in 1895.

Matthijs Vermeulen could barely play any instrument and couldn't afford a piano until he was 23, but he was determined

to become a composer. Daniël de Lange, the director of the Amsterdam Conservatory, recognized his talent, and gave him free

composition lessons for about two years. His financial situation slightly improved when Vermeulen started to write

concert reviews for the newspaper De Tijd. His personal tone,  flamboyant style and sharp musical judgement stood out immediately, and through these

articles he was brought into contact with

Alphons Diepenbrock, the most prominent Dutch composer of that day. Diepenbrock,

born in 1862, was a composer with a broad musical horizon, who predominantly wrote for the voice. Having started of in

a more or less Wagnerian idiom, Diepenbrocks music gradually became more lucid and transparent, often possessing poetic,

dreamlike qualities, as does his Marsyas, which originally

was incidental music for a play by Balthasar Verhagen, first performed in 1909. Or he struck a more somber and severe tone,

as in Elektra, the last piece Diepenbrock

was to compose, before his death in 1921. Vermeulen would always refer to Diepenbrock as his 'maître spirituel'.

flamboyant style and sharp musical judgement stood out immediately, and through these

articles he was brought into contact with

Alphons Diepenbrock, the most prominent Dutch composer of that day. Diepenbrock,

born in 1862, was a composer with a broad musical horizon, who predominantly wrote for the voice. Having started of in

a more or less Wagnerian idiom, Diepenbrocks music gradually became more lucid and transparent, often possessing poetic,

dreamlike qualities, as does his Marsyas, which originally

was incidental music for a play by Balthasar Verhagen, first performed in 1909. Or he struck a more somber and severe tone,

as in Elektra, the last piece Diepenbrock

was to compose, before his death in 1921. Vermeulen would always refer to Diepenbrock as his 'maître spirituel'.

While establishing himself as a music critic, Matthijs Vermeulen in the meantime completed his first composition,

between 1912 and '14: the

Symphonia Carminum, the symphony of melodies. For an opus one, this is truly

a remarkable work. Not often will a composer have begun his career with such a large scale piece, containing music

that breaths such a strong sense of urgency and endeavour. The broad musical gestures and large polymelodic structures

immediately strike the ear. The music sounds a bit too much like unhinged Mahler though, and the overall form of the piece

and its sense of direction are still far from perfect. But it are particularly the melodies, restlessly hovering and

meandering in multiple directions that stand out, and make one feel that Vermeulen had found his voice immediately.

In 1915 he showed the work to Willem Mengelberg, a step that must have puzzled the conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra,

because by that time Vermeulen had already published numerous articles in which he ferociously attacked Mengelberg.

In Vermeulen's opinion, Mengelberg's choice of repertoire leaned too heavily on the German symphonic tradition, and he felt

that Mengelberg neglected the modern French masters, Debussy and Ravel. And he scorned Mengelberg for his frequent absence

from the Concertgebouw, to conduct the orchestras in Frankfurt and elsewhere.

After taking a brief look at the score of the First Symphony, Willem Mengelberg affably advised Vermeulen to take a few composition lessons

with Mr. Dopper, his assistant-conductor. This was in fact not entirely meant as a sarcastic word of advice. Because, not

only was Cornelis Dopper a very frequently performed composer at that time, but a closer look at Vermeulen's score also reveals

numerous spots that are impractically and clumsily notated, due to his lack of experience and education. One might certainly

blame Mengelberg though, for failing to look through these imperfections, and to recognize the authentic voice that sheltered

underneath the surface and deserved to be heard. This word of advice was enough to make Vermeulen rush off, deeply insulted.

Some years later, he would seek his revenge with Cornelis Dopper: On a Sunday afternoon concert in November 1919, in the brief

interval right after the final chord of Dopper's Zuiderzee Symphonie

had faded away, and just before the applause was

about to start, Vermeulen got up from his seat and shouted : "Leve Sousa!!!"

After taking a brief look at the score of the First Symphony, Willem Mengelberg affably advised Vermeulen to take a few composition lessons

with Mr. Dopper, his assistant-conductor. This was in fact not entirely meant as a sarcastic word of advice. Because, not

only was Cornelis Dopper a very frequently performed composer at that time, but a closer look at Vermeulen's score also reveals

numerous spots that are impractically and clumsily notated, due to his lack of experience and education. One might certainly

blame Mengelberg though, for failing to look through these imperfections, and to recognize the authentic voice that sheltered

underneath the surface and deserved to be heard. This word of advice was enough to make Vermeulen rush off, deeply insulted.

Some years later, he would seek his revenge with Cornelis Dopper: On a Sunday afternoon concert in November 1919, in the brief

interval right after the final chord of Dopper's Zuiderzee Symphonie

had faded away, and just before the applause was

about to start, Vermeulen got up from his seat and shouted : "Leve Sousa!!!"

"Long live Sousa!" A nice piece of instant and concise musical criticism, in which Vermeulen expressed that the virile march

music of John-Philip Sousa, that was to boost

the morale of American troops stationed in Europe, was far to be preferred above

the drab mediocrities of Dopper's Zuiderzee Symphonie. This unexpected outburst caused great consternation among the

audience. The commotion was even further enhanced, because part of the people in the hall thought that someone had yelled "leve

Troelsta!". Jelles Troelstra

was the leader of the Dutch Socialist Party, who had just a week earlier, unsuccessfully staged a

coup d'etat in the Dutch parliament, by proclaiming a takeover of power by the proletariat. The police came in, and Vermeulen

was expelled indefinitely from the Concertgebouw by the management. Vermeulen's First Symphony would not receive its

first performance until 1964. There was in fact one performance in 1919, by the Arnhemse Orkestvereeniging, but this was such a

dissatisfying experience, due to the many mistakes in the parts and reluctance on behalf of part of the orchestra, that Vermeulen

refused to consider this to be the première of the piece.

With his four anti-war songs in 1917, Matthijs Vermeulen found a more receptive audience. Particularly

La Veille, on a poem

by François Porché, received a fair number of performances by the Belgian mezzo-soprano

Berthe Seroen, who at that time was living in

exile in the Netherlands, which had remained neutral during the First World War. La Veille, the wake, portrays a lonely woman,

praying at the cradle of her baby, on the night before a battle. When at dawn the soldiers march by, she bids farewell to those who are

about to die. The music of La Veille possesses extremely meditative and lyrical qualities and is perhaps the most powerful example

of Vermeulen's abilities as a composer of vocal music.

With his four anti-war songs in 1917, Matthijs Vermeulen found a more receptive audience. Particularly

La Veille, on a poem

by François Porché, received a fair number of performances by the Belgian mezzo-soprano

Berthe Seroen, who at that time was living in

exile in the Netherlands, which had remained neutral during the First World War. La Veille, the wake, portrays a lonely woman,

praying at the cradle of her baby, on the night before a battle. When at dawn the soldiers march by, she bids farewell to those who are

about to die. The music of La Veille possesses extremely meditative and lyrical qualities and is perhaps the most powerful example

of Vermeulen's abilities as a composer of vocal music.

After Vermeulen had completed his Second Symphony in 1921, he again approached Willem Mengelberg, this time by mail. There

came no reply at all. Vermeulen left for France, hoping his music would find a better response there. But again, he was disappointed

to find out that the revolutionary élan of the first decades of the 20th century had washed away, and that neo-classicism had become

the reigning musical fashion in Paris. Disillusioned, he settled with his wife and four children in the small village of Louveciennes,

where he would remain in a sort of self chosen exile for over 25 years, in relative anonymity and poverty.

The Second Symphony, of which we will listen to a brief section shortly, consists of five contiguous movements, which Vermeulen

calls episodes, that alternately have an active and contemplative character, while they are all related to the same basic tempo of 88 beats

per minute. The third and the fifth episode are related to the first, in the sense that elements of the main theme are further elaborated.

The piece starts of with four measures of percussive, cluster-like chords in the low strings, before the introduction of the main theme,

which is played in octaves by four oboes, five clarinets and two trumpets in e flat, together producing a marvelous, icy sound. The theme

in its entirety actually consists of three phrases, punctuated by chords in the low woodwinds and brass, while the cluster-like chords

keep on pounding along. This section is followed by a variation on the theme with the use of parallel harmonies, first in the lower register,

and then in a very wide spacing of four octaves plus a minor second, between the high clarinets and the contrabassoon and bass clarinet.

The music then gradually becomes more polyphonic, before culminating in a recapitulation of the theme, again in unison, but this time

spread out over four phrases. So, let us hear now, if my brief analysis of the first episode of the Second Symphony was more or less accurate:

Second Symphony, main theme

Second Symphony, main theme

To me, Vermeulen’s Second Symphony is like a momument. Not only because it marks the birth of modern music

in the Netherlands, but mostly because of its wild and exuberant world of sound. In this piece Vermeulen has completely cut

himself loose from tradition and tonality and created a musical idiom that is entirely his own. With its relentless energy,

ecstatic outbursts and violently passionate melodies the Second Symphony truly seems to prelude to a new day. One

can hear some resemblances with Edgar Varèse's Ámeriques and Arcana, works that were written more or less

around the same time. They share the same kind of obsessive drive and power, though Vermeulen's symphony lacks the elaborate

and sophisticated writing for percussion, which gives to Varèse's music this wonderful sensation of Italian Futurism. Also,

some parallels can be drawn with the music of Charles Ives, with regard to the use of polymelodic structures and to the fact

that both of them were Einzelgänger, musical loners, who ostentatiously and stubbornly went their own way.

About his vision on music, Vermeulen wrote : "There has, amidst of the schools, styles, mannerisms, tricks and formalisms

that pass by, along with the conventions on which they supported, always been a sound that lasted. That would not let itself

be determined by its year of origin, before or after Christ, that stood outside of all times and peoples, that unchangeable,

indestructible came into life, that will never decline, and whose magic will never end. One recognizes this sound immediately

and everywhere, because it is immediate and everywhere; one is defenseless against it, because it is, with its primitive and

rudimentary accents, born into every soul, because everybody carries it inside himself, because it has always cried or sang

in this manner, from the caveman to the man of our mechanical age. It is also the single, inexorable, powerful, magical tone.

It is the only thing worth for a composer to strive for." Vermeulen wrote these words in his essay Antipodes, in which

he also tried to describe Willem Mengelberg's 'characterological unfitness' for the French repertoire.

The fundamentals of Vermeulen's ideas are formed by a social humanism, that leaves its traces in all of his creative output.

He assumes music to have an utopian function. Already from the titles which he gave to his symphonies: Les Victoires,

Les Minutes Heureuses, (the joyous moments) Dythyrambes pour les Temps á venir, (hymns for the times to come)

or Les Lendemains chantants,(the songs of tomorrow) one can sense a strong desire for the glorification and liberation

of the soul. The place where the destiny of mankind is to be given shape is the orchestra, which is conceived as a musical

community in which all of its heterogeneous voices and groups, although moving in the same direction, can freely develop.

In an interview with the New York Times in the 1920's, Willem Mengelberg characterized the Dutch music of those days as "either

to be watered down Wagner, watered down Debussy, or watered down Mahler". If we take into account that at that time Vermeulen's

music was hardly ever to be heard, this is in fact a very accurate description. "The Dutchman", as composer and critic Willem

Pijper would put it, "has always diligently imported his wine, his grain, his tobacco and his music, and doesn't really know

any better than that it should be like this. He is certainly not unwilling to come to understand that a Dutch music could be

just as excellent as a French or Austrian, but his ears would have to convince him of that first. The Dutch merchant will buy,

if necessary, on a sample, very rarely on the basis of just a picture, but never on an anonymous recommendation." Still today,

it is the case that a Dutchman, or woman, that excels in any given field, will only get any recognition from his fellow countrymen

once there has been some success abroad. If such is the case, then he or she must be good. Apparently the Dutch don't attribute

much value to their own judgement.

But the general idea that the Dutch audience, in the days when Matthijs Vermeulen started of as a composer, was of a conservative,

petit bourgeois and unadventurous nature, is based on a misconception. Because if we take a look at which composers

frequently passed by at the Concertgebouw between, let's say, 1905 and 1915, we see that Gustav Mahler practically lived there,

Arnold Schönberg, Claude Debussy and Richard Strauss were regular guests, and that the likes of Igor Stravinsky, Max Reger, Maurice

Ravel and Alexander Scriabin were also to pass by. I think it is fair to say that the Dutch audience in those days had a far more

adventurous taste than its composers, with the exception of course of Matthijs Vermeulen and, to a lesser extend, Alphons Diepenbrock.

Probably even now, one hundred years later, many an orchestra around the world, would be somewhat reluctant to put together concert

programs with the aforementioned composers, out of fear that they might startle a substantial amount of their subscription holders.

But the general idea that the Dutch audience, in the days when Matthijs Vermeulen started of as a composer, was of a conservative,

petit bourgeois and unadventurous nature, is based on a misconception. Because if we take a look at which composers

frequently passed by at the Concertgebouw between, let's say, 1905 and 1915, we see that Gustav Mahler practically lived there,

Arnold Schönberg, Claude Debussy and Richard Strauss were regular guests, and that the likes of Igor Stravinsky, Max Reger, Maurice

Ravel and Alexander Scriabin were also to pass by. I think it is fair to say that the Dutch audience in those days had a far more

adventurous taste than its composers, with the exception of course of Matthijs Vermeulen and, to a lesser extend, Alphons Diepenbrock.

Probably even now, one hundred years later, many an orchestra around the world, would be somewhat reluctant to put together concert

programs with the aforementioned composers, out of fear that they might startle a substantial amount of their subscription holders.

The way the Dutch audience regarded the contribution of Dutch composers to these programs however, was that they were something like

an appetizer, or a side-act: First some watered down Wagner, or watered down Debussy, and then came the real stuff. On the concert

at which the 'Long live Sousa!'incident took place for example, the Zuiderzee Symphonie of Cornelis Dopper was intended to

warm up the audience for the Brahms Violin Concerto, which was to take place after the intermission.

The mistake that Matthijs Vermeulen made, and I must stress here that the word mistake is in this case intended in a one hundred

percent ironical fashion, is that he wanted to break away from this convention. Because it was his belief, and rightly so, that his

music was not at all watered down, but that it was the real stuff. He felt, that by following his inner voice, regardless of what

went on in Paris, Vienna or Berlin, and without making faint attempts at folklore to achieve some sort of a Dutch nationalistic style,

like most of his native colleagues, he had actually reached a free, liberated and independent Dutch music, that had broken away

from provincialism and irrelevance. Vermeulen, as a matter of fact, wrote this, more or less ad verbatim, in the letter that accompanied

the score he sent to Willem Mengelberg, recommending him his Second Symphony. And this also sums up, why I greatly admire

Vermeulen as a composer.

It is difficult to calculate, or even to try to estimate, the damage and harm that the writer Vermeulen has brought upon the composer

Vermeulen. I think, it would be an understatement to say that the one surely did not help the other. Throughout all of Vermeulen's

writings runs the same lyrical and exuberant vein, that is also so clearly audible in his music. Sometimes he could be very right

on the mark, perhaps not very pleasant for the subject of his criticism, but sometimes things simply needed to be said. The Concertgebouw

Orchestra, for example, organized a grandiose Mahler-festival in 1920, to honour and commemorate the composer, who had died in 1911,

and to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Mengelberg's affiliation with the orchestra. All of Mahler's works were to be performed,

in a celebration that attracted a massive amount of international attention. Vermeulen read in the program book that "Mahler had gone

to the United States with the intention to save up a small fortune, and then to return to Holland, which had been so dear to him,

and where his music had found such a good response, and then had wanted to settle in a nice, quiet place, to devote all his time to

composing."

Matthijs Vermeulen subsequently wrote: "I was thinking : Willem Mengelberg, who has often been proclaimed to be such a good friend

of Mahler, could have had knowledge about the dire situation his friend was in, and could have proposed to the Concertgebouw-management,

that in a low estimation represents a capital of twenty million guilders, to connect his friend Mahler to the Concertgebouw, let us

say, for a fee of ten thousand guilders, with the obligation to conduct ten concerts a year. Mahler, the tired, haunted and worn down

Mahler, would have accepted such an offer with both hands; And we, we would have made ourselves useful to one of the most genius

artists of all times."

Matthijs Vermeulen subsequently wrote: "I was thinking : Willem Mengelberg, who has often been proclaimed to be such a good friend

of Mahler, could have had knowledge about the dire situation his friend was in, and could have proposed to the Concertgebouw-management,

that in a low estimation represents a capital of twenty million guilders, to connect his friend Mahler to the Concertgebouw, let us

say, for a fee of ten thousand guilders, with the obligation to conduct ten concerts a year. Mahler, the tired, haunted and worn down

Mahler, would have accepted such an offer with both hands; And we, we would have made ourselves useful to one of the most genius

artists of all times."

But after the First World War broke out, Vermeulen's judgement, which by nature had always had more of an inclination towards the

French camp, gradually became more blurred and irrational. At a certain point, any French composer, be it a second- or third-rank

composer like Fauré, Delibes or Lalo, was always still better than the best what Germany had to offer. This is for example what

he had to say with regard to Johannes Brahms' Fourth Symphony, around 1916 : "spineless and muscle-less plastic of a

crippled. Did Brahms possess a deep nature? No, he never felt the pain, because he was used to always avoid himself from it. How

then, can he ever have learned the fullness of joy ? Brahms will inevitably still often be played and admired for a couple of years,

but it is our conviction that within a foreseeable future, he will have become old-fashioned and ridiculous. Brahms is a fashion,

that will disappear like the winter gives way to the summer." It was Mengelberg's conviction on the other hand, that it was the quality

of the music that counted, and not the country where the passport of its composer was issued.

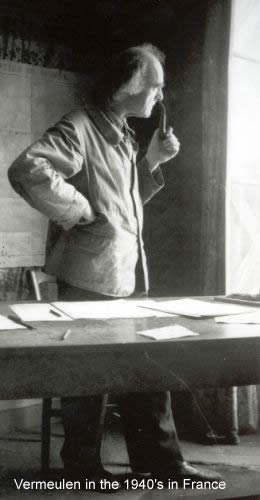

During his long period of exile and isolation in France, Vermeulen went through a compositional drought that lasted for nearly ten

years. But in 1930 came, out of the blue, a commission for the celebration of the 355th anniversary of the University of Leiden, in

collaboration with the poet Martinus Nijhoff.

The latter came up with the theme, after he had seen an advertisement of the KLM, the

Dutch airline company, reading : "The Flying Dutchman. Once a legend, now reality." The performances of De Vliegende Hollander

were held outdoors at a lake. The action took place on a boat, the audience was seated ashore. The windy conditions washed away nearly

all of the music, but it brought the composer Vermeulen back on his feet, and he produced three more symphonies in the next fifteen years.

Willem Mengelberg in the meantime continued his triumphs, with the Concertgebouw Orchestra and orchestras all over the world. The outbreak

of the Second World War in 1940, and the occupation of the Netherlands by Germany, limited his ability to move. Apart from some concerts

in the Third Reich, he was bound to Amsterdam. Willem Mengelberg did not make more than some faint signs of protest, when in 1941 the 16

Jewish musicians of the Concertgebouw Orchestra were sacked. And Willem Mengelberg, I will quote Matthijs Vermeulen here once more, "who

has often proclaimed to be such a good friend of Mahler", did not make any objections whatsoever, when in 1942 the plaque bearing

Mahler's name, along with those of Mendelsohn and Rubinstein were removed from the Concertgebouw. After the war, Mengelberg got a six

year ban on conducting, He died, in his châlet in Switzerland, just before the end of this period. Mengelberg was as politically naïve as

he was a great musician. The pitiable ending of his fifty years of tenure, still hangs like a cloud over the manner in which the greatest

conductor the Netherlands ever had is remembered. When in 1995 there was a new Mahler-Festival at the Concertgebouw, one hundred years

after Mengelberg first took the stand, Riccardo Chailly, then the principle conductor of the orchestra, thought it was a good moment

for a re-evaluation of the man who had made the orchestra what it is. The management rushed in, downplaying the mere idea of a rehabilitation,

out of fear that controversy might drive away sponsors and the audience.

Matthijs Vermeulen received two serious blows in 1944, when first his wife died and then his son Josquin, the apple of his eye, while

fighting in the French Liberation Army. In 1946, Vermeulen returned to the Netherlands, taking up his old profession as a music critic.

1953 brought the long awaited première of the Second Symphony, in Brussels, and from then on it went crescendo molto with the

appreciation of Vermeulen as a composer, who in 1955 made his debut with his Second Symphony at the Concertgebouw Orchestra,

which was conducted by Eduard van Beinum.

I have always found it intriguing that from the moment Vermeulen started to hear his compositions being performed in the concert hall,

his new musical output became less interesting to listen to. The Second Symphony is a masterpiece, there is no other word for

it. But in the Fourth Symphony 'Les Victoires'

, the orchestral textures already start to clot and to thicken in such a manner that it withholds the

listener a clear view of what is going on. The arches of tension become longer and longer, and then also start to overlap with one

another. And by the time we have reached his Seventh, and last symphony, it is, as critic Ernst Vermeulen (not related to the

composer) once put it, "as if you keep on eating and eating a plate of spaghetti, that somehow never seems to become any emptier."

Reinbert de Leeuw, the conductor, pianist and composer, is one of the few musicians still alive, that have worked with Matthijs Vermeulen,

before his death in 1967. I asked de Leeuw, about whom we will hear more in the second lecture, what Vermeulen was like in person. He

told me: "I first met Vermeulen in 1963, when I was still a Conservatory-student, to rehears his

Cello Sonata no.1, together

with René van Ast, for a concert to celebrate his upcoming 75th birthday. He had an extremely warm, gentle and generous character, with

very precise ideas about how he wanted things to sound. We went for long walks, through the fields and the heather, where he would

hold endless and very well articulated monologues on his ideas of music. He knew no doubt, and he was absolutely convinced that the

course of musical history would have taken a entirely different path, had his music been performed forty years earlier. But what I

remember most of all about him, is that there was no trace of bitterness or anger, not even the slightest hint."

Reinbert de Leeuw, the conductor, pianist and composer, is one of the few musicians still alive, that have worked with Matthijs Vermeulen,

before his death in 1967. I asked de Leeuw, about whom we will hear more in the second lecture, what Vermeulen was like in person. He

told me: "I first met Vermeulen in 1963, when I was still a Conservatory-student, to rehears his

Cello Sonata no.1, together

with René van Ast, for a concert to celebrate his upcoming 75th birthday. He had an extremely warm, gentle and generous character, with

very precise ideas about how he wanted things to sound. We went for long walks, through the fields and the heather, where he would

hold endless and very well articulated monologues on his ideas of music. He knew no doubt, and he was absolutely convinced that the

course of musical history would have taken a entirely different path, had his music been performed forty years earlier. But what I

remember most of all about him, is that there was no trace of bitterness or anger, not even the slightest hint."

Matthijs Vermeulen rejected the music and ideas of Schönberg, he rejected the music of Stravinsky. And while living in France, he was

all the time in the vicinity of Olivier Messiaen, with whom he could have had, I am sure, interesting discussions on music and spirituality,

or on the relation between music and the destiny of mankind. Of course they had different views, on many things. But, isn't that exactly

what it takes to come to an interesting exchange of thoughts? Such discussions never took place, Messiaen and Vermeulen never even met.

Because he rejected the music and ideas of Messiaen. Gradually, he came to reject the music of Debussy, of Mahler, Ives, Varèse, and I

could go on endlessly to list all the composers, who Vermeulen thought had it all wrong. That is what I meant at the beginning of my

talk, when I said that Vermeulen wanted to be an outsider. And though I have the greatest respect for the unshakeable faith Matthijs

Vermeulen has always kept in himself and in his ideas, in spite of the opposition he encountered along the way, I also feel that if you

reject all of contemporary music, besides your own personal output, you are dangerously close, just one step away, from a total

rejection of contemporary music at large. I thank you for your kind attention, and am looking forward to see you again.

©Robert Zuidam

Harvard, Erasmus Lectures no.1, February 18 2010